This is a review, if a review is meant to be written wide-eyed, a little uncertain of reality, of Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves. Known for being a scary cult novel approximately the size of the Argos catalogue, it is somewhat imposing. I started reading it last night, got about twenty pages in, and then today I continued reading and, in amongst other tasks like decanting homemade sloe gin, I read the whole thing. So I may be a little intense.

House of Leaves is 700 pages of text about an apparent documentary, footnotes both scholarly and telling stories in good postmodern style, appendices, pictures, and typographic display that can leave you dizzy. Each layer of the story – loosely the tale told in and by the documentary, the story of the writing and compilation of the main text by Zampanò, and the discovery, introduction, and notes by Johnny Truant – questions its own reality and others, meaning that reading the book basically requires a reader to question both nothing and everything. This is partly what makes it compelling: the sense that there might be a truth, or no truth at all, keeps you reading through chapters full of gaps from apparent scorchmarks or scientific analyses mostly lost.

The reading experience is perhaps the most important part. With its footnotes and appendices (some of which you are directed to only to discover there is nothing there), there isn’t quite an exact way to read House of Leaves. For example at one point, the option to read an appendix giving childhood background to the editor (who tells his own story in his footnotes) is offered, but to take this option is to read a series of letters that themselves form a not so simple story. The effect of this experience is to draw you into the uncanny, to be looking for where you must read next and whether it will be part of a narrative or a list of notable buildings that exist. It is more like an immersive experience.

Unnerving is perhaps a good way to describe House of Leaves. The layers of narrative and their layers of uncertainty mixed with a vast amount of fictional academic debate and references to real and fictional texts mean that the reading experience becomes unnerving, as expectations are denied and the nature of a text questioned. In my opinion, what is scarier than the stories within the book are the stories and parts of the narratives left on the outskirts, the ones in your peripheral vision and the ones that happen as you interpret what you read.

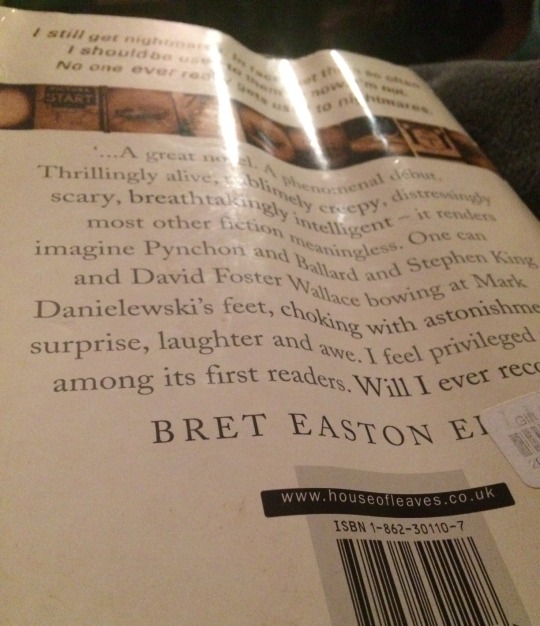

If these paragraphs haven’t convinced you yet, it is not an easy book to describe or recommend. I would say it is like a cross between the Lunar Park end of Bret Easton Ellis, Nabokov’s more postmodern stuff, and a confusing critical book about some abstract concept that uses popular references to try and explain its points. There’s mythology, horror, academia, and the kind of contemporary American novel where everybody takes so many drugs you lose track. House of Leaves is worth reading, though perhaps not in a day.

(As apparent here, my secondhand copy has the added uncanny fact that it has a huge mysterious wave/dent running through it.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.