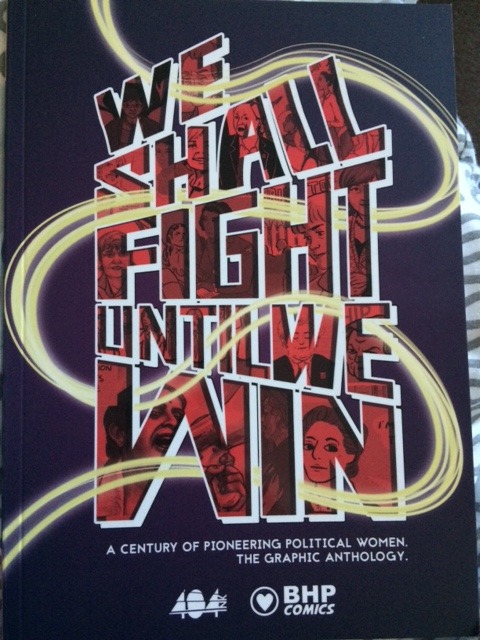

We Shall Fight Until We Win is a graphic anthology showcasing the lives of political women for the centenary of the first wave of women in the UK gaining the right to vote. Female writers and artists have come together to create short comics only a few pages long that tell the stories of women both well-known and lesser-known who have been engaged in politics in the UK and beyond.

The stories told in the book are wide-ranging, diverse, and often fascinating. This is an anthology that doesn’t shy away from the difficult topics, highlighting where the subjects of these comics have held questionable ideals. Many people may see the inclusion of Margaret Thatcher and question her place in the anthology, but actually the piece in question is about the fact she did not fight for women. Telling women’s political stories must include the less savoury elements as well. Alongside this, there is a focus on lesser-known figures and those often reduced to tiny notes in the margin of history (excellently covered in one comic) or silenced altogether.

It isn’t difficult to see that We Shall Fight Until We Win is an important anthology that engages with women involved in politics and activism in the UK. The short comics are moving and readable, making them an ideal way to engage people not interested or able to read a huge book about female political history, and the artwork is quirky and memorable. Once you read it, you’ll be thinking of more and more people in your life that need to read it as well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.