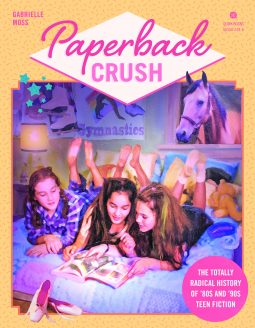

The Totally Radical History of ‘80s and ’90s Teen Fiction

Paperback Crush is a fascinating and funny look at American teen fiction from the gap between Judy Blume and Harry Potter. Moss divides up the books by themes, and looks at how areas such as romance, friends, school, and fear sparked off a whole range of books aimed at the young adult and middle grade market. There’s plenty of focus on how well the books actually dealt with big (and small issues), but Moss writes with a witty, light-hearted tone too, combining nostalgia, light mocking with hindsight, and some actual analysis of how the trends worked and fitted into the framework of young adult fiction that came before and afterwards.

As someone who is both British and too young for these books’ heyday, the real selling point was the ‘Terror’ chapter, as I was a great lover of first Goosebumps and then, even more intensely, Point Horror (Moss’ point that the students at Salem University from Diane Hoh’s Nightmare Hall series should’ve just dropped out felt like a ‘oh, right, they should have’ moment, because I did not think that at the time of reading them). However, the whole book was an enjoyable read, a quick look through a kind of book that shaped a lot of people’s lives and have had an impact on the young adult fiction of today. Moss’ tone makes it funny and engaging, but Paperback Crush is also an interesting look at how these often flawed books did deal with topics that some may assume only modern YA does. Plus, it has a lot of pictures of hilariously bad paperback teen novel covers with witty commentary.

You must be logged in to post a comment.