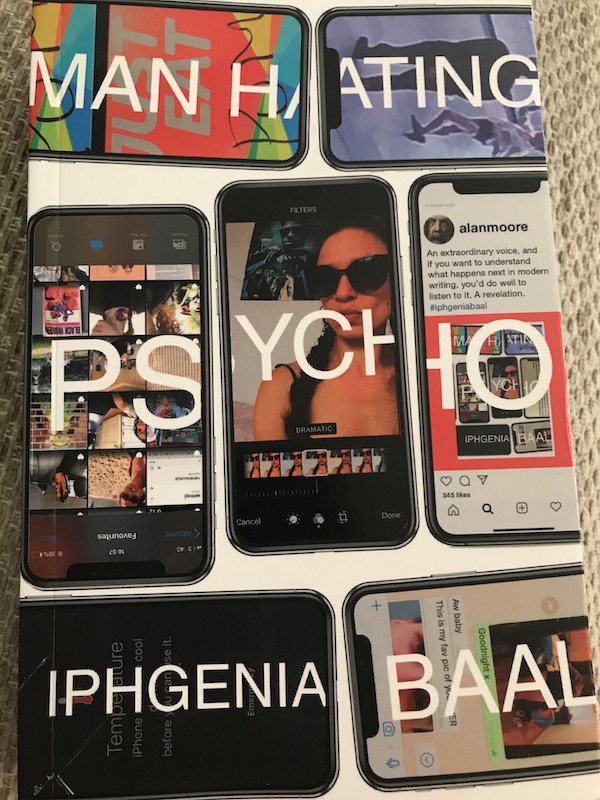

Man Hating Psycho is a collection of short stories that in many ways are the anti-short story, or at least anti-something. From a Labour activist group chat gone wrong to a take on an apparently “‘inverted’ psychogeography’, the thirteen texts look at modern London, technology, relationships, and people trying to be subversive.

The chaotic cover and blurb drew me into the collection, despite being someone who doesn’t always gravitate towards short story collections unless they’re doing something a bit different or telling a wider story. I’d say in some ways Man Hating Psycho fulfils both of these categories, with stories that feel like a fresh take on the form and an overarching sense that it’s saying something biting about modern life and London. It certainly kept me gripped throughout, never sure what the next piece might bring, and enjoying the fact most of the stories didn’t end with a clever conclusion, as it feels a lot of short stories have to, but something more like a freeze frame or fade out.

The first piece, ‘Change :)’, is an ideal opener, a story in group chat form that depicts a modern political moment and an amusing technological fail. Other stories that stood out to me personally were ‘Pro Life’, a slice of teenage life going off the rails, and ‘Married to the Streets’, the previously mentioned take on psychogeography and changing London. One or two of the others were a bit long and meandering for my tastes, but I enjoyed the narrative voices and style throughout, and the little cutting barbs directed at various topics.

For fans of short stories and also people who are more ambivalent towards the form but want to try something different, Man Hating Psycho is a gleefully spiky collection that shows the mostly downs of modern London.

You must be logged in to post a comment.